Holstein–Primakoff transformation

One of the very important aspects of quantum mechanics is the occurrence of—in general—non-commuting operators which represent observables, quantities that we can measure. A standard example of a set of such operators are the three components of the angular momentum operators, which are crucial in many quantum systems. These operators are complicated, and we would like to be able to find a simpler representation, which can be used to generate approximate calculational schemes.

The original[1] Holstein-Primakoff transformation in quantum mechanics is a mapping from the angular momentum operators to boson creation and annihilation operators. As can be seen from a paper with about 1000 citations, this method has found widespread applicability and has been extended in many different directions. There is a close link to other methods of boson mapping of operator algebras; in particular the Dyson-Maleev[2] technique, and to a lesser extent the Schwinger mapping.[3] There is a close link to the theory of (generalized) coherent states in Lie algebras.

The basic technique

The basic idea can be illustrated for the classical example of the angular momentum operators of quantum mechanics. For any set of right-handed orthogonal axes we can define the components of this vector operator as  ,

,  and

and  , which are mutually noncommuting, i.e.,

, which are mutually noncommuting, i.e., ![\left[S_x,S_y\right]=i\hbar S_z](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a78c0fec10ce3b6669f91a67c1231674.png) and cyclic permutations. In order to uniquely specify the states of a spin, we can diagonalise any set of commuting operators. Normally we use the SU(2) Casimir operators

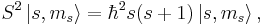

and cyclic permutations. In order to uniquely specify the states of a spin, we can diagonalise any set of commuting operators. Normally we use the SU(2) Casimir operators  and

and  , which leads to states with the quantum numbers

, which leads to states with the quantum numbers  :

:

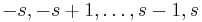

The projection quantum number  takes on all the values

takes on all the values  .

.

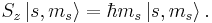

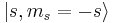

We look at a single particle of spin  (i.e., we look at a single irreducible representation of SU(2)). Now take the state with minimal projection

(i.e., we look at a single irreducible representation of SU(2)). Now take the state with minimal projection  , the extremal weight state as a vacuum for a set of boson operators, and each subsequent state with higher projection quantum number as a boson excitation of the previous one,

, the extremal weight state as a vacuum for a set of boson operators, and each subsequent state with higher projection quantum number as a boson excitation of the previous one,

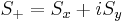

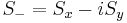

Each added boson then corresponds to a decrease of  in the spin projection. The spin raising and lowering operators

in the spin projection. The spin raising and lowering operators  and

and  therefore correspond (in some sense) to the bosonic annihilation and creation operators.

therefore correspond (in some sense) to the bosonic annihilation and creation operators.

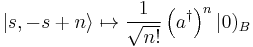

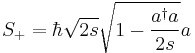

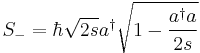

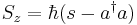

The precise relations between the operators must be chosen to ensure the correct commutation relations for the angular momentum operators. The Holstein–Primakoff transformation can be written as:

The transformation is particularly useful in the case where  is large, when the square roots can be expanded as Taylor series, to give an expansion in decreasing powers of

is large, when the square roots can be expanded as Taylor series, to give an expansion in decreasing powers of  .

.

Physical Subspace

The difficulty with any of the boson mapping techniques is the fact that we have a physical and unphysical space: Any state with more than  bosons is a perfect bosonic state, but does not correspond to an angular momentum eigenstate. When acting on such a state, the argument of the square root in the definition of

bosons is a perfect bosonic state, but does not correspond to an angular momentum eigenstate. When acting on such a state, the argument of the square root in the definition of  is negative, and hence is imaginary. If a truncated Taylor expansion of

is negative, and hence is imaginary. If a truncated Taylor expansion of  is performed, this would be missed.

is performed, this would be missed.

References

- ^ T. Holstein and H. Primakoff, Phys. Rev. 58, 1098 - 1113 (1940) http://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.58.1098 DOI: 10.1103/PhysRev.58.1098

- ^ A. Klein and E. R. Marshalek, Boson realizations of Lie algebras with applications to nuclear physic,s http://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/RevModPhys.63.375 DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.63.375

- ^ J. Schwinger, Quantum theory of angular momentum, Academic Press, New York (1965)